When Hurricane Sandy battered the eastern seaboard of the United States in 2012, a storm surge caused catastrophic flooding of Verizon’s central office (CO) in Broad Street, Manhattan. Miles of underground copper cables were ruined by the water. Even worse, paper insulation in the wiring sucked water deeper into the network through capillary action, destroying cables in otherwise dry areas. Verizon found that it was too difficult, expensive and time-consuming to rescue the existing copper network, so decided to rewire with optical fibre cables instead.

The CO wasn’t Verizon’s first experience with switching off copper. In August 2011, Verizon had retired the copper facilities in its Bartonville, Texas, location after a review of company records indicated that no carriers were using them. But Hurricane Sandy forced Verizon to take a deeper, harder look at the benefits of optical fibre; and that information spurred the incumbent to pursue an extensive decommissioning plan. By early 2016, Verizon said it had successfully converted 35,000 customer lines in 22 COs across six states (New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey and Virginia) with plans to reach more than 2,000 locations.

Verizon says the fibre-optic technology not only supports service improvements, but ‘delivers increased reliability, improved resistance to water/moisture and faster repair times’. Indeed,

the operator says service dispatch rates (to fix faults) are 85 per cent lower on new fibre networks compared to copper, with obvious cost savings. FTTP networks are lower power and take up less space. When its ‘Network Transformation’ is complete, Verizon will no longer need as much as three quarters of the CO real estate it holds.

Targeted copper retirement

More than five years has now elapsed since Hurricane Sandy but, perhaps surprisingly given the documented benefits, few operators have followed Verizon’s lead. Many are still concentrating on the operational challenges of rolling out their FTTH networks; while some countries have complete coverage by FTTH networks, this is not yet the norm. Some operators may be hoping that ‘natural migration’ – as more customers abandon copper products in favour of faster fibre broadband services – will make the transition process much simpler in the fullness of time.

Where operators do pursue a more extensive copper switch-off programme, the motivation is not always what you might expect. For instance, Telkom, in South Africa, is so keen to get the copper out of its network, after suffering customer outages following numerous incidents of copper cable theft – more than 6,000 in 2015 – that it is replacing legacy networks with both fibre and wireless alternatives (though not at the same time). As the price of copper goes up, it becomes a commodity that someone wants to steal; even more reason for incumbents to replace those wires with optical fibre.

Elsewhere, operators tend to be selective in how and where they switch off the copper. Canada’s Sasktel has been deploying FTTP since 2011, gradually bringing in new fibre connections when work is carried out on the copper network. Single customer migrations are taking place where there have been repeat service repairs. Where a municipality requests the removal of utility poles, the operator is using the opportunity to initiate the ‘cut over’ from above-ground copper wires to underground fibre.

Retirement benefits

Industry analysts believe the debate around copper switch-off needs to move up a gear. ‘What our members highlight to us is the difficulty in keeping two networks running at the same time because it is very costly,’ said Marta Capelo Gaspar, director of public policy for the European Telecommunication Network Operators Association (ETNO), speaking at the FTTH Conference in Valencia, Spain, earlier this year.

Yves Blondel, from telecoms consultancy T-Regs, said: ‘There’s an economic dimension. Verizon articulated to investors that there would be a substantial cost saving. It is widely understood, as well, that fibre networks are likely to be greener in terms of not using as much electricity. These points are not debateable. So, when do we get to the stage where we stop talking about copper migration and carry out that migration?’

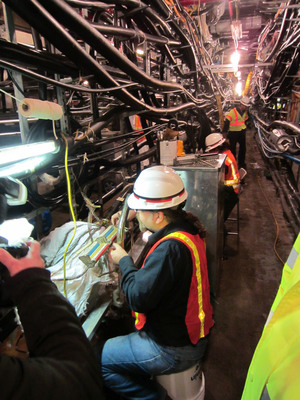

By early 2016, Verizon said it had successfully converted 35,000 customer lines in 22 COs across six states. Credit: Verizon

‘No fibre to the home plan by an incumbent is complete without a scenario about copper switch-off. And yet precious few incumbents seem to even be considering the question,’ said Benoit Felten, chief research officer at Diffraction Analysis. ‘Managing two networks in parallel to serve the same customers is nonsensical. Sure, an operator can view fibre as a premium product, only offered to the wealthy few, but there’s no significant profit in that. Fibre to the home is a scale game.’

Big decision

That doesn’t mean switching the copper off is a trivial decision, though: in many cases copper products are resold to competitors through unbundling, who will resist change because they fear losing their customers or their investment in equipment. Regulation usually prevents the network owner from unilaterally shutting down the copper and kicking the wholesale access seeker off the network. Regulators will insist on alternative provision. But even when alternatives to unbundling have been made available, it’s a huge disruption for everyone.

Spain has been the fastest country to build out FTTH in Europe, with fibre-optic cables now reaching 31 million premises – more than France, Germany, the UK and Italy combined. Telefónica plans to consolidate and close legacy copper facilities where it deploys fibre, but progress is slow. Under regulations established in 2009, Telefónica is obliged to offer unbundled copper services for a period of five years after filing a decommissioning request, to give wholesale customers time to move to alternative products. The process can only be accelerated in facilities where there are no wholesale customers; the first batch of planned closures in 2015 were small COs, where the local loop was not shared.

The five-year notice period arises from the European Commission’s Recommendation of September 2010 on Regulated Access to Next Generation Access Networks (NGA). In 2012, Orange France launched a ‘100 per cent Fiber’ pilot in Palaiseau, a suburb of Paris with around 17,000 households, to assess and anticipate the challenges associated with copper switch-off. One of the reasons the Palaiseau experiment failed to progress was because Orange was unable to negotiate an earlier date with alternative operators to close down the main distribution frames where the latter had installed their equipment; this meant Orange was obliged to maintain wholesale access until 2018.

In the United States, copper retirement rules have been in place since 2003, and (after some revisions in 2015 and 2017) mandate a shorter, six-month notice period for both retail and wholesale customers, as well as suitable replacements for legacy services. Regulatory

authorisation is not required unless copper retirement will also result in a discontinuance of service (where there is no like-for-like service replacement). So, it could be argued that Verizon faced fewer regulatory hurdles to its copper retirement plans.

No more dial tone

Tightly linked with the challenge of copper switch-off is the migration of the public-switched telephone network (PSTN) – which has provided dial-tone telephony services for the past 100 years – to newer packet-based technologies. This has proven to be a complex organisational and technical challenge for operators, which has taken longer to implement than anyone originally thought. A case in point: UK incumbent BT said it wanted to be the first major operator to switch off its PSTN, and its 21 Century Network was designed to support this ambition; but while BT now has a perfectly good packet-based core network, PSTN services won’t be turned down until 2025.

Twisted-pair copper cables were an integral part of the original PSTN; but they can also remain part of the network in a next-generation access deployment, in fibre to the cabinet, node or distribution point strategies. Many operators have pushed ahead with fibre deployment while leaving the PSTN intact. That’s going to become an increasingly difficult position for telecom operators to maintain, as the cost of operating two networks – one circuit-based, one packet-based – will continue to increase, especially as it becomes more expensive to repair out-of-service equipment and the skills base needed to maintain old equipment becomes lost.

The question of what to do with the copper is more pressing as FTTH roll out becomes more widespread. ‘Many operators who started this [FTTH deployment] years ago are now in the 40–50 per cent take rates in areas where they have deployed fibre. The question of what to do with the copper becomes acute,’ said Felten. Operators should see the deployment of fibre in the access as a golden opportunity to switch customers to packet-based services at the same time. In practice, the two upgrades do not always align.

While a lot of copper to fibre migration has already occurred, there’s still a massive task ahead for the incumbents. ‘We may be talking about copper to fibre migration for the next 10 to 15 years,’ said Blondel.

Main image credit: Verizon